By Uche Onyebadi

YOUR idea of a war veteran might well be that of a fairly old man, an old soldier, retired, with friends and family around him, gleefully telling and re-telling gripping tales about escapades at the battlefield. You might be right. But, that picture of a war veteran might not match a typical, modern war veteran in the United States.

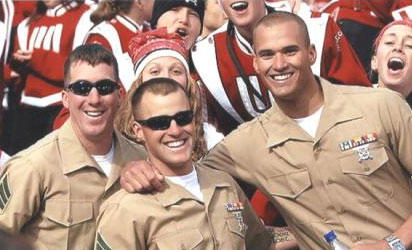

Many a time, such veterans are men and women approaching their prime, not necessarily people at the dusk of their life; people in their twenties or thirties who have seen enough warfare in the terrible terrains of Afghanistan and Iraq. A large population of these former soldiers come home with brutal, physical scars of the wars they were compelled to fight out of a sense of patriotism. But many more bear invisible scars that are no less tormenting. And, quite a good number of them who say no mas to the agony in their souls often opt out of this world by committing suicide.

It may appear quite unbelievable, but the statistics show that about 22 United States war veterans, old and young, take their lives on a daily basis simply because the pact they signed with life had gone sour. Oftentimes, they snap and quit the wretchedness that was their living on earth. And most of them die so young. A young man named Clay Hunt from Texas was one of such young men snapped up by suicide at a young age. He was only 28 years old when he committed suicide in 2011. Like so many of his colleagues who had passed on, his problem was that of suffering from the dreaded post-traumatic stress disorder. It is the silent killer of veterans who, ironically survived the trenches in Vietnam, Korea, Afghanistan and Iraq only to come home and die uncelebrated.

You wonder why this suicide rate is so high and why these veterans who put their lives on the line for their country do not adequately get the help they need when they come home. Some months ago, I wrote in this column that these soldiers are “Heroes abroad, destitute at home.” They suffer a high rate of unemployment as some employers are wary of hiring ex-soldiers for a number of unstated reasons. Cases of the post-traumatic stress disorder rose to an all-time high of about 21,000 in 2012. In a report released by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, a huge number of 57,849 homeless veterans was recorded on one brutally cold winter night in January, 2013.

The irony is that on their campaign trail, practically every U.S. politician will pledge to do something to take care of the veterans and “wounded warriors” as the injured among them are proudly called. But, that pledge ends there. Even getting medical help is a huge problem for most of these wounded warriors. Last year, the CNN reported the ungarnished fate of these veterans at a veteran’s hospital in Phoenix, Arizona. The nation was shocked to learn that up to 40 veterans die while on the waiting list to see their doctors. That scandal led to the resignation of General Eric Shinseki as the U.S. Secretary for veteran affairs. But, the clamour for him to go and his eventual decision to step down has not radically changed anything.

Nevertheless, something is now being done to redress the fate of U.S. veterans, at least to tackle the rampant suicide incidents. Last week, President Obama signed the “Clay Hunt” law whose sole aim is to provide help to veterans in order to curb their tendency to commit suicide when hopelessness overwhelms them.

Challenging process

The law was significant in two ways: It was passed by the highly partisan U.S. Congress, an indication of how serious the issue had become since Congress cannot agree on anything else; the law acknowledges the fate of Clay Hunt whose parents campaigned over the years for government to come to the aid of veterans, using their son’s case as an example of the negligence the former soldiers go through upon their return home.

Upon signing the law last week, a concerned President Obama remarked that “This law will not bring Clay back, as much as we wish it would. But the reforms that it puts in place would have helped, and they’ll help others who are going through the same challenging process that he went through.” If the opportunity provided by the new law had existed, then the likes of Clay might not have opted to take their own lives. Mr. Richard Selke, stepfather to the dead warrior told reporters after the law-signing ceremony that “what this bill does is take away some barriers, some needless barriers, that shouldn’t be there and make it easier for these veterans to get the health care they’re so entitled to.”

That may be what the veterans are entitled to, and much more. But the bureaucracy along the way has been insurmountable. Here is how Jake Wood, who had served in Afghanistan with Clay, marshaled his argument after the signing ceremony: “How can we have 22 veterans committing suicide every day in this country, and that’s not a national issue? This is an issue that needs to be seared into the forefront of every citizen of this country.” His contention should be viewed against the reality that 15 members of his Marine unit in Afghanistan have so far committed suicide after their tour of duty.

One thing is to have signed the law aimed at halting the suicide rate among America’s brave hearts, yet implementing the law will fall into the hands of the same administrators and workers at the Veteran Affairs unit. Having fought and survived a war, only to come home and take your life in frustration, is not a good testimony of how any nation should treat its men and women of valour.

Disclaimer

Comments expressed here do not reflect the opinions of Vanguard newspapers or any employee thereof.