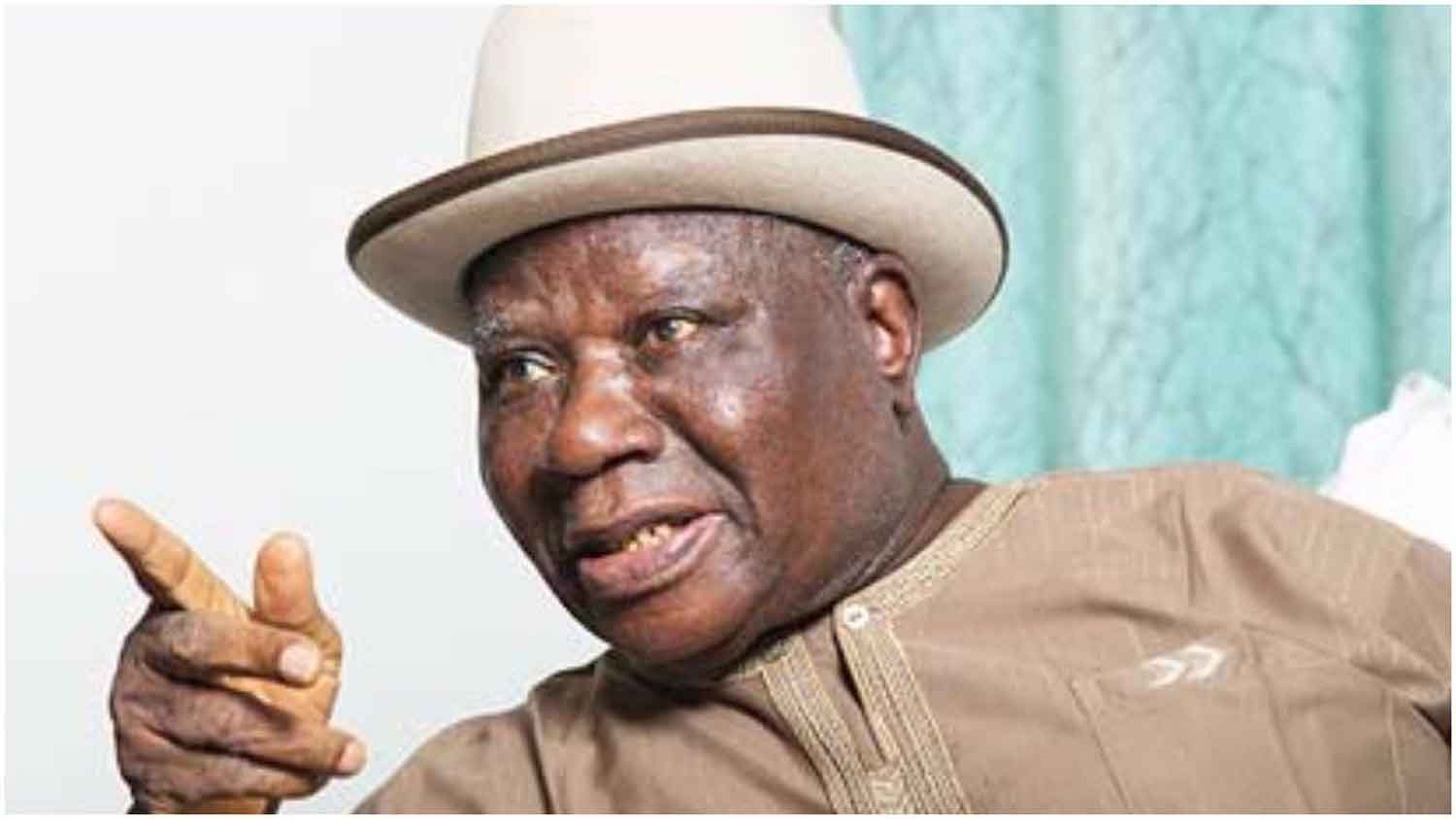

Edwin Clark

•Says great grandfather married 100 wives

•’Narrates how teacher changed his name to Edwin Clark, named brother, Prof JP Clark, Johnson

• ‘Life as a night crawler, dancer, singer in London’

• Regret: I lost daughter to breast cancer

By Henry Umoru, Assistant Politics Editor

Chief Edwin Kiagbodo Clark (E.K. Clark) has great credentials: a lawyer, an administrator, Ijaw National Leader, a nationalist,a freedom fighter, leader, South-South Peoples Assembly, leader, Southern and Middle-Belt Leaders Forum, SMBLF, and leader, Pan Niger Delta Forum, PANDEF. He was Commissioner for Education, Mid-Western Region, 1968-71; Commissioner for Finance and Establishment, defunct Bendel State, 1972-75; Federal Commissioner for Information, 1975; and Senator, 1979-83. In this interview, the Kiagbodo-born elder statesman, who turned 97 on Saturday, May 25, bares his mind on growing up, philosophy, ambition, influence of parents, how rascally he was as a young man, achievements and regrets, among other things. Excerpts:

You are 97. How is it like?

To be 97, I think, with all sense of humility, it does not come to me as a surprise. I have been like this. I may say, for the past five years, I have not changed. So, I have been looking forward to it, and I knew that, last year, I was 96, May this year, nothing has changed in me. I am happy that May 25 is my 97th birthday, but it does not come to me as a surprise, but to thank God for making it possible for me to reach that day. When I look back, that is why I said I thank the Almighty God who has made it possible for me to create this record of 97 in my family, the entire family. My great-grandfather, Bekederemo, who was one of the wealthiest merchants in this country, not Niger Delta alone, he was very wealthy to the extent that, as I said the other day in my book, he married a hundred wives and recognized all his children, and I am the first great-grandson. He did not live up to 92 or 93, same with my grandfather, Fuludu, who managed his father’s business for a considerable length of time. He was wealthy on his own too. He died at the age of 87, 88. Then my father and my mother, both of them, I think they died at the age of 85, 86 or so. Looking back at my background,I am the first man in the family to attain the age of 97, that is the record I have set. Also, I have discovered that none of those people I mentioned, my great-grandfather, grandfather, my father, none of them became the oldest man in the community. But, today, I am the oldest man in my clan. And so, there is one thing I was actually looking forward to, growing older, older, I was thinking about great-grandchildren. Four years ago, perhaps when I was 93, I was praying to the Almighty God that there was one line that is remaining perhaps, that I should have great-grandchildren. As I speak to you now, between the age of 93 and today, I have got four. I thank God that He has given me fulfilled life, which makes me feel happy at all times. I pray God to continue to keep me healthy, perhaps if I got the batteries, give me many more years.

How was your growing up?

My growing up, in those days, when we were in our time, I’m talking about 97 years ago… Your mother gets married to your father, and the first child, or even more, when your mother is going to have a child, she will leave the husband’s family house, and go home to her mother to stay, and have the child there. So, that is what happened in my own case. My father was from Kiagbodo. My mother came from Eruwanrhien. Eruwanrhien is a village very close to Kiagbodo. And my mother’s mother, Komuno, was a descendant of, was the daughter of Ufo. Now, Komuno’s mother is from Ovwian. They called us Agbayin in those days in Udu local government council. We have a family, I descended from Onosohwo family. So, growing up, I was born in Eruwanrhien. My grandmother at that time was alive and took care of us until she died. I think she died around 1935 or so when I was still staying there in Eruwanrhien, I was not going to school. But we had village teachers who would come and teach us for some time, these were not organized and then our parents paid fees, but we didn’t know what we were learning really. Now, my brother, Ambassador B.A. Clark, who died September last year, grew up with me, he was born in 1930 when I was only three years old. This is one question I have always asked, I wanted to find out, family planning in those days was very natural, my mother’s children were born every three years, two children every three years, there was no medical or anything. One was not able to find out how they did it that you have Edwin Clark in 1927, you have B.A. Clark in 1930, you have J.P. Clark in 1933, I think you follow what I mean. They were not organized planning. I don’t know what happened in those days. I grew up with my grandmother, but when she died, I stayed with my uncle, called Oguri. I’m going to tell you a funny story. Oguri, my uncle, was a very big fisherman, very industrious, he would go throughout the night, and early in the morning arrive with canoe filled with fish, fresh ones and so on. Then I was just about nine, 10 or 11, something happened, he asked me to go to the water side, to bring the fish from the boat. So I went, then I found out that some of the fishes were not dead, were still alive, so as I was carrying them, I was trying to play with one and it just got out of my hand, back into the water and swam away. I started crying, there was no way to get the fish back. My uncle returned and came to the water side. He said, “Kiagbodo, what are you doing?” So I told him. He said, “You are crying because of fish? Tomorrow I am going to catch this particular one for you, carry the fish, let’s go home”. I still remember that moment.

Visiting Kiagbodo

When we were about 10 to 11 years old, my father came and took us back, took us to Kiagbodo; that was the first time we were visiting Kiagbodo. I spoke Urhobo more than Ijaw, my father’s language. Then he said, “Now you are going to stay with my mother at Effurun-Otor and go to school there”. Meanwhile, my small brother, Professor J.P. Clark, had been taken there at the age of five and he was there. We went to Effurun-Otor, then we went to school, African Church School, and we were under a teacher called Thompson Okitikpi. We had no teachers apart from him, he was the only teacher, single man, he was the headmaster, he was the class teacher. And one day he called the four of us, me and my other brothers, he said, “It’s very difficult to pronounce Kiagbodo, pronounce all your names. I want to give you an English name. Kiagbodo, you are now Edwin Clark”. “Godfrey”, he called one of my brothers, he’s dead also, “you are Godfrey Clark”. Then Bill, his name was Akporode Clark, and he changed it to Blessing Clark. Then he said, “Pepper”, my professor, “your name today is Johnson”. These are the names we answer till today, they were not given to us by our parents; that’s how we grew up. And when in 1940, my father said “no, we should go to Ijaw school”, there was a very prestigious school opened by the government called Native Authority School, Okrika and children were brought from various places to attend that school. He said that we should go there and there we should be able to speak Ijaw which we did. We were very young at the time and one question we asked ourselves, “Are we going to stay with somebody, a master or a madam?” And with our father before that day, we took a lot of firewood, ground pepper, groundnut, everything, fish and so on. My father said, “We are going to Okrika tomorrow”; so we went. The people received him being a chief. But then he said, “I want someone who is very, very strict, who is a disciplinarian, I want him to take care of my children, but not to live with him, they will take care of themselves, they will cook”. And somebody asked, “These children will cook?” He said, “Well, they should cook what they want to eat”. That’s how we grew up. We were living together in Okrika. We cooked our food, we did everything. On weekends, our mother will come, bring palm oil, everything, cook for us, no refrigerator, so we must cook everyday or if you want to cook to eat, then you boil it very well so that it will not get sour, tomorrow morning, you boil it again and you eat it. So, we had that humble background and we will swim in the river, then we will dive to catch crabs or Kpoku (oyster) and snails, we used them in cooking. At that time, fish was in abundance, but not today. If I tell you, you won’t believe it, I have never tasted iced fish; when we were growing up in Okrika, sometimes we found fishermen drying big fish and small fish in the fire and, sometimes, we would go to the water side after eating to watch them and go back home. Sometimes, when we were watching, the whole place would be filled with fish, we would take those fish and go back to eat at home, so, we lived a very good life and so on.

Moving Hospital

But when we were in school, then I was the Class Monitor, I discovered for the first time that there was what we called Moving Hospital, that is, doctors from Forcados with nurses, with other dispensers and so on, who toured the various schools, there were very few, but they were held in a very high esteem by the colonial administrators. The doctors would come to our school, test us, every person would go in to undergo test. As a result of that, most of the doctors, I knew them even though I was young. We had Dr. H.A.A. Doherty, I still remember, I’m talking about something of over 70 years. Then we had Dr. Williams, a Yoruba man, Dr. Henry Adefope. Now, in Dr. Adefope’s case, when in 1975 I was appointed Minister of Information or what you called Federal Commissioner for Information, among those who were to be sworn-in that day, there was this man, this Dr. Henry Adefope; so I was looking at him. I went to him, “Sir, may I know your name?” He said, “My name is Dr. Henry Adefope, Maj. Gen. Henry Adefope. I’m in charge of the medicals in the Nigerian Army”. I said, “Sir, did you at any time in your life serve in a hospital called General Hospital Forcados?” He said “yes, I was there in 1943”. I said, “That’s so, then you were my doctor”. He said, “What do you mean?” I said, “I was one of those you examined, I was then about 12 to 13 years old”. So he embraced me, some people were curious; we were meeting for the first time. So, you can see how God works, you can see how God changes people’s lives. One must give glory to God at all times; today, I am telling you part of my success story.

Tell us your philosophy and ambition when you were growing up?

Well, number one, I was the first son of my father and, like I also said, I was the first grandson of Fuludu Bekederemo and I come from a very large family. That leadership quality, that’s how I developed it from my parents. My mission in life was to help my people, to see that my people were educated and that is why, today, by the grace of God, the Ijaw ethnic nationality made me their leader. And I remember in 1975 when I was appointed Minister by Gen. Yakubu Gowon, the entire Ijaw invited me in March of that year to Bomadi, the whole tribe, pensioners, inspectors of police, commissioners of police, they were all there and I was given the chieftaincy title Izon-Ibe Kikilowe, the Ijaw man who was taking care of the Ijaw tribe, and that’s the title, the first title I had in my life. So, being very patriotic while growing up, taking responsibility, knowing the background, my family background, I think I had something. I was never afraid of anybody, fearless means I should not be afraid of anybody. I remembered it when I was listening to Wigwe’s University, this word, fearless, I saw that he (the late Wigwe) too liked that word; so I’m only afraid of God, not human beings. I respect human beings. At a very young age, I served my people. There is no single village or town in Delta State, the present Delta State or Delta Province, that I did not visit, that I don’t know totally. Even during the census of 1973, I was riding in a helicopter visiting villages, educating them and I was to travel to Kpakiama, an Ijaw town, the President of the National Congress, Professor Kaba, that is his village, I was to go there. At the end of the census, they said the population was larger than the accepted ones and that there was over counting; so I was to go there, visit there to know what happened. And that beautiful day, I had dressed up in Warri to be picked up by the helicopter, but as I was coming out, the ground was slippery and I fell. Several people said “don’t go again”, so I did not follow the white driver. In the evening, news came that the driver crashed on the road and he died. I would have not been saying this or talking to you now if I had traveled in that car, so you can see that I have every reason to continue to thank God, the Almighty God.

Were you rascally when you were young?

Well, you can imagine that I was rascally. In those days as we were growing up, some of us became Warri boys, and, as Warri boys, we were rascally. Every Christmas we would dance round the town and during the New Year, the same thing, so I was rascally. But I was also very responsible as the first son, I must show example to others. But I was not dumb; I was not the type that would just keep quiet. I have always spoken my mind right from the beginning.

Are you not always afraid for your life when you confront the authorities?

No, but let me give you another example. In 1952, I think the Governor of Western Nigeria, Sir John Ranking, visited our college at Abraka, Government Teacher Training College, Abraka, and so we all gathered, he addressed us. Then he said “any question from anybody?” I stood up, our principal was a white man; he wanted to stop me. The Governor said “let him ask his question”. I said, “Your Excellency, I wanted to know from you why only some traditional rulers are given the knighthood of the British Empire and our people are not given and politicians like Azikiwe, Awolowo are not being given?” But as he wanted to answer, the principal intervened and, at the end, the man left; in the evening, we were to have dinner, we were gathered in the dining hall with the Monitor or the Prefect, Asagboyin, from Ubiaja, in Edo State today. Then a military man who had gone into the college to be a teacher called my name, so I stood up. He said, “You come out and there was a table in the front and he said I should mount the table. So, he asked me why I should ask the question I asked the Governor. I said “what is wrong?” He said everything was wrong. So, they punished me, they asked that I should wash plates of all the students every evening for five days, which I did. But one of the senior teachers, Isekwe, from Inla, who was our physical education teacher, called me, gave me palm wine, he said I should drink it. I said I did not know what it was; he said, “Drink it. You will be a great man”. I said “how?” He said, “What you did two days ago pleased many Nigerians who were in that hall. So, don’t mind your fellow students”. So I’ve always been very active. Not rascally, I am sorry. Another occasion I still remember was in 1961. I arrived in London, and the British institute, which took care of students, placed them in hostels and so on, they came to the airport to pick us. We were taken to Number 1 Hans Crescent, along Knightsbridge, the most expensive area of London; we were over 200 students from all over the world: Australia, Canada, West Indies, Nigeria, East Africa and Kenya. Indians, Malaysians were there too, a combination of Nigerians and some of my mates. I did know some of them, we were about seven. I think one or two of them are still alive. Some of these Supreme Court judges lived with me in that hall. One day, they said we were going to have an election because every year there must be a new President of the student organization there to liaise with the British Council on how to take care of the place. I said, “Very good. Who is going to be our candidate?” They said “you are going to be our candidate”. I said “no, no, I just came from Nigeria”. But they voted for me to become the President of Hans Crescent. Normally you spent one year in that office. But they voted for me for two years. I have always had qualities of leadership, of being noticed at all times, but it is not my making. That’s God’s work.

What are your greatest achievements in life. And regrets, if any…

My greatest achievement in life, really, is what is going to happen on Saturday (97th birthday). That’s my greatest achievement, of being allowed by the Almighty God to reach the age of 97, that’s my greatest achievement.

Any regrets?

Once you are a man, you must have regrets in your life: Regrets that you have lost a daughter, regrets that you have lost some children, regrets that you have lost a father, a mother, regrets that you have lost friends, regrets that you have not done something to prevent something from happening. And, when it happens, you show regrets; so there are always regrets in one’s life. Perhaps one of the occasions, I had a daughter called Herenta Wilkimba Clark. She was married to one Sowore in Lagos and they did not tell me that she had cancer of the breast and she was expecting a baby. And without consulting me, I was far away, running about politics with President Goodluck Jonathan and so on. I didn’t know that my daughter had been operated upon in Warri. I was very upset. I said she should be flown to London. So, she went there, had the baby, she was well. They tried to take care of her. Then she returned to Nigeria to do a few things, I had to go to London for my medical check-up.

I was there when my brother, Professor J.P. Clark, phoned me and said, “Wilkimba is not looking fine. Her eyes are yellowish, all sorts of things”. I said, “Well, I am in London, send her to me”. She came to London with the daughter, four-year-old girl. I was to come back to Nigeria, I took her to hospital. She said, “Daddy, are you leaving me?” I said, “Yes. You know, as a leader, people will take care of you here”. She said, “Will you do me a favour? Look after my daughter. Don’t let someone else take her. I am very grateful for all that you have done for me”. One week after I arrived here, she died. That girl of four years is now 17. I am educating her; that was it. I regretted having lost a daughter and I am happy that I have a granddaughter who is a carbon copy of the mother. Therefore, in one’s life, there are ups and downs. Sometimes you are happy, sometimes you regret. But that’s how life is.

Do you like music?

Ah, I like music very well. When we were in London, we used to go to clubs, dance and all types of dances we used to dance. I sing very well. But it is of the past now and I’ve always thanked God, I’m always a happy man.

Your great-grandfather had 100 wives. Let’s talk about your own wife, children. Are you romantic?

I don’t know what you mean by that. I have children. I have almost 30 grandchildren now. I have four great-grandchildren, I told you. And I have about 10 surviving sons and daughters. I am a happy man.

What is your message to Nigerian youths?

My message to Nigerian youths has always been, this is our country, nobody is brought to life by God to be dependent on someone else forever. Nigerian youths should realize that we were all youths before; I told you I was a Warri boy. In those days, when Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, as a politician, in 1947 or even 1957, was coming, we would go out of Warri, 11 miles, to wait for him to arrive from Lagos. And we would stop the car, we would be dancing on the ground. We had been youths before. But none of us at that time knew you will become a minister, a governor or president, nobody knew. My advice to Nigerian youths is that you should be grateful to God that you were born as a Nigerian son or daughter, and you have a duty therefore to work very hard in whatever capacity you can. Education is the key to the success. All our Nigerian youths, I think the best thing to do is have good education, once you have acquired good education, the road will be opened for you. I am advising our youths to be patient, not to run after money, not to run after drugs, because your time will come. You don’t know what God plans for you, when the time comes, nobody can stop it. No human being created by God can change the course of another man’s life, except with the permission of God, and God will never permit it. That is it. So, my advice to youths is that your day will come. Meanwhile, be a good citizen of your country. Do not rush after money that you have to carry politicians’ bags and so on. It won’t help you. The God that made me what I am will also make you what you will be, even better. That’s my advice, to be resilient, not to worry themselves that nobody has made their lives. Even twin children, they live different lives. So no two persons will live one type of life.

Disclaimer

Comments expressed here do not reflect the opinions of Vanguard newspapers or any employee thereof.